BY CHARLES MPAKA

For 17 years now, politicians have systemically destroyed Malawi’s agriculture by reducing the lead ministry into a “subsided fertilizer distribution institution”, officials in the ministry have complained.

And while politicians have been pouring money into fertilizer subsidy, they have literally emasculated the department by underfunding all its core functions, budget details show.

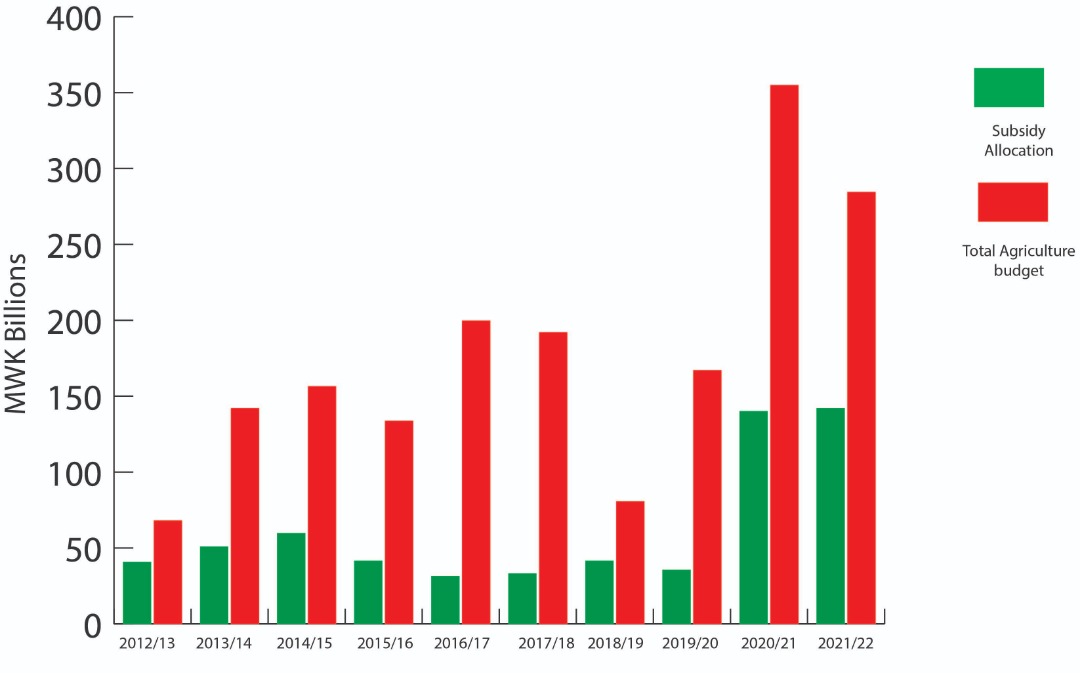

In that period, they have allocated over K708 billion towards maize fertilizer subsidy alone, according to figures we have collected from budget analyses and statements covering the past 17 years from 2005 when the programme started.

That year, the subsidized fertilizer programme got a modest 17.6 per cent of the agriculture budget.

But the craving to give out cheap fertilizers rose in 2006 when the allocation jumped to 32 percent of the sector budget.

Since then, the programme has gobbled up between 30 and 59 percent of agriculture budget in over 12 of the 17 years.

This has effectively condemned all the ministry’s components to survive on crumbs falling from the table of fertilizer subsidies.

Interestingly, coming in amid long-standing calls for the government to start scaling down the programme en route to exiting it all together so that funding is freed to the ministry’s core functions, the Lazarus Chakwera administration has instead dramatically pushed up subsidy spending.

Of that estimated K708 billion, the new administration’s fertilizer subsidy share constitutes 40 percent in just two seasons.

Last year, it put K140 billion in the programme, quadrupling the K35.5 billion of the 2019/2020 financial year. That K140 billion was 39.4 percent of total agriculture budget.

This coming financial year, while many departments have suffered massive budget cuts, it has pleased Treasury to allocate K142 billion to fertilizer subsidies, representing 49.9 percent of the agriculture budget.

The ministry is structured to develop Malawi’s agriculture through the following technical departments: animal health and livestock development, agriculture planning services, agriculture research services, crops development, fisheries, irrigation development, land resources conservation and agricultural extension services.

But with politicians treating fertilizer subsidy as the kingmaker in their empire, these core components have had to survive on leftovers of public funding.

All along, politicians have said their objective in implementing the subsidies is to ensure food self-sufficiency, hence the lion’s share in funding. However, the driving motive – election votes – reflected out of the statement by Minister of Finance, Felix Mlusu, recently.

At a post-budget meeting with Economics Association of Malawi in Blantyre two weeks ago, he indicated that politicians do know that the programme exerts enormous pressure on the public purse, hence the need to exit it.

But he also hinted at how the thought about election votes prevents them from exiting the programme.

“Obviously, this was a campaign promise we made. We have done this in one year…, it cannot make sense for us to scrap it come second year,” Mlusu was quoted in The Nation as having said.

Spokesperson for the ministry, Gracian Lungu, admitted to PIJ the funding biasness towards subsidies.

“It is indeed true that for some good years, a good chunk of agriculture budget goes to subsidy.

“The status has remained like this for a reason that [ministries, departments and agencies] basically follow what the governing leader sees in his/her vision of transforming the country,” he said.

A senior ranking official at Capital Hill told us that politicians have put the ministry in their vote-buying vice, overwhelming technocratic sense and stifling the ministry from its core mandate.

He admitted that subsidies have constrained agriculture development in Malawi because “focus has been on production alone with nothing on processing and marketing which could have spurred development and growth through increased income and further investment.”

He added: “Focus on subsidies has also been done at the expense of investments in research and extension [and] no substantial changes in technologies farmers have been using over the years.”

This, said the source, has led to slow growth of agriculture in Malawi against a background of emerging challenges such as climate change.

He further said subsidies – which some see as a political financing and appeasement mechanism owing to politically-linked firms that line the supply chain — have not only crowded out public spending but also charmed private sector out of participation in agro-industrial development activities in favour of quick fertilizer subsidy windfall.

And it looks like the ministry is forever in the grip of the politicians, going by what Lungu said.

“For us as a ministry, we will always do according to the vision of our leaders in line with MW2063,” he said.

Collapsed Frontline

And, in what sounded like resignation to the politically-driven public spending imbalances to the sector, Lungu said going forward, they will be focusing on lobbying the NGO sector to help in areas “where we are still having challenges so that all departments under our ministry should tick as a whole.”

It means that all the components in the sector may continue to be in the margin of public funding if fertilizer subsidy is not exited or reformed.

At the heart of all that Malawi desires to achieve in agriculture are extension and advisory services; but we can report that extension services in Malawi are suffering badly under the weight of fertilizer subsidy largesse.

As development economist and Chief Executive Officer for Africa Institute of Corporate Citizenship (AICC), Dr Felix Lombe argues, by their very nature, extension workers “should and ideally must work with farmers at all stages of the value chain activities that farmers undertake”.

“Everybody agrees that [FISP/AIP] should culminate into increased productivity, increased food security, increased access to market and increased value addition. But increased productivity means modern farming technologies and climate smart methods. This is where extension work comes in,” he said, adding:

“In a nutshell, FISP/AIP should have been tools in the hands of extension workers and not a replacement of extension services.”

In practice, in terms of funding and general government attention, the subsidy programmes have literally replaced extension services.

In its official documents, Capital Hill acknowledges the moribund state of component at the moment.

It admits that it has been providing limited financing to extension services due to what it says are “competing needs for same resources”.

“This has been manifested in limited-service delivery, inadequate maintenance of extension workers’ offices, houses, limited staff capacity building, low provision of potable water, no access to electricity, and poor means of transport for staff especially at grass-root level,” says Capital Hill in a recently-developed National Agriculture Extension and Advisory Services Strategy (2020-2025).

While extension services, like other areas in the ministry, have been starving, fertilizer subsidy programme has been swimming in public money, literally.

For instance, one study by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) found that between 2007 and 2012, Malawi spent 52 percent of the agricultural budget on fertilizer subsidies, but only one percent went to extension services in that period.

The pressure of this underfunding is being brought to bear on the ground.

In the past two months, we have visited a total 30 subsistence farmers individually in Lilongwe, Machinga, Zomba, Kasungu and Dowa to appreciate extension services activities on the ground.

We have also examined District Social and Economic Profiles (SEPs) and other records covering 20 of the 28 districts of the country, alongside speaking with several district agriculture officers and extension workers.

We can report that underfunded, understaffed and ill-equipped, extension services are standing on fragile legs at every level.

All the 20 districts we covered fall way down government’s own recommended ratio of one extension worker to 750 farmers.

For instance, Zomba has 49 extension workers against the requirement of 150 and Machinga has 57 extension workers while it needs 140 extension personnel.

In Lilongwe and Kasungu which are considered the bastion of agriculture in Malawi, the situation is as bad. According to their SEPs, Lilongwe’s field officer to farmer ratio is 1: 1,436 while Kasungu’s is at 1: 3,334.

In Mulanje the ratio is at 1:4,287, Dowa at 1: 3,046, Mzimba North at 1: 1,750 and Chikwawa at 1:1,259.

And while the subsidy programme is said to target the poorest and those in remote-lying locations, we found that these are less likely to be reached by extension services, let alone locate where they can find an extension worker or demand their services.

When asked why she does not demand extension services to assist in her farming, a woman farmer in Mayaka in Zomba said: “Do I even know what I am getting wrong? What I know is that I have been unable to produce enough maize in the 6 years that I have been getting this fertilizer.”

Stretched with workload, the available few extension workers have to contend with a raft of challenges in their work, a situation which they have officially made known to the authorities.

In one of their petitions dated 10 July 2020 and addressed to Minister of Agriculture, Lobin Lowe, the extension workers complain that they are struggling with mobility.

The petition also says the ministry has overdue salary arrears for some field officers starting from 2014 and that some of them enter and retire from the system without any change in their grade.

We can also report that the extension workers are struck in the decentralization maze, with no definite authority to come to their rescue.

While the Ministry of Agriculture is their mother employer, every time they press for solution to their challenges, they are shunted across ministries of labour, finance, local government and Office of President and Cabinet.

And after years of pushing to be heard, they hoped the new administration would assist them at last, only for it to leave them grasping at straws again, as even the current budget under debate in Parliament has not attended to their concerns, they say.

And now frustration is palpable.

“The [subsidy programme] invests more cash from our [agriculture] budget but demotivates extension services. The ministry has turned into an institution for distributing fertilizers,” said Isaac Kwisongole, General Secretary for Agriculture Technicians Union (Atum), Isaac Kwisongole, a grouping of agriculture extension workers in Malawi.

‘Not worth the huge sums of money’

Director of Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources for Machinga district, Nditani Maluwa, said politicians have killed Malawi’s agriculture, in their obsession with fertilizer subsidies programme which he said is also being implemented wrongly.

“It’s not just about handing out fertilizer that will deliver this country from food insecurity. There is also the question of skills and knowledge transfer for efficient use of that fertilizer and adoption of more effective farming practices. This is where you need extension service workers,” he said.

He laughed off politicians bragging rights about high figures of maize harvest which they claim are a result of the subsidies. According to Malawi, what Malawi is producing is not worth the huge sums of money it is putting in.

“That’s why 17 years on, beneficiaries of subsidy cannot be weaned off. We have destroyed farmer knowledge and skills systems. Most of our farmers are producing 2.5 tonnes on a piece of land they could have produced 10 tonnes if extension services were reliable and efficient.

“So, fertilizer subsidies are giving us less than they should while we are also using them to kill agriculture in general. We can’t go anywhere like this,” he said.

‘When subsidy drains out last coins’

According to Lombe, subsidies everywhere are political solutions. But Malawi’s, he said, is a very difficult one.

“When a subsidy drains out the only remaining coins from your own revenue as a government, then you need to revisit the whole scheme and take a painful decision,” he said.

Lombe said excessive interest and deep obsession with subsidies will only delay Malawi’s realisation of her dream of agriculture commercialisation as contained in the MW2063.

He added that the money which is being invested in fertilizer subsidies could have been put in components such as livestock and fisheries development, agro-processing, irrigation and mechanisation.

And he scoffed at government’s idea of ‘sub-contracting’ extension services to NGOs. He said NGO-led extension is often inefficient and shallow in scope and coverage.

“In fact, it only succeeds in overstretching and burdening the same public extension system. You may want to know that many NGOs rely on the same government agents. Getting lured by allowances, these public agents end up abandoning their formal scope and everyday work,” he said.

Furthermore, Lombe argued, NGOs do not have the full technical capacity in this space, hence have introduced untested methods often imported from elsewhere and imposed by donors.

“That’s why today, there are too many untested technologies dumped on farmers by NGOs, leading to confusion and contradictions on the ground. Since NGOs have money, they ultimately succeed in confusing and contradicting what government would have loved to do,” he said.

He urged government to be bold enough and invest in extension services without being bullied by anyone on the size of public administration.

Watch out for the next series of this investigation

.png)